© text and images courtesy of the Arnold Arboretum Library - Harvard College

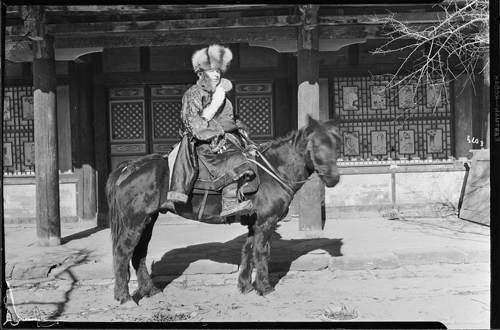

Tibetan - Moslem War in West Kan-su, text by Joseph Francis Rock

In central West Kan-su, on the Hsia Ho or Summer River, rises on its north bank the famous and largest of all Lamaseries of West China, it comprised many hundreds of small houses, the abodes of nearly 5.000 monks and 80 incarnations was ruled over by a small boy of ten summers. The name of this famous Tibetan monastery belonging to the yellow reformed church was Labrang Trashi ch’ il. The boy god whose residence towered over all the other buildings was a native of Li-thang (Chinese Li-hua) in Hsi-k’ang, and during his minority his father, a former bandit according to the Mu-li King, was regent. The boys incarnation was known as Laughing Jamb-yang and was his fifth, the first being the founder of the monastery which comprised forty six large stone buildings, some four storeys high. It was a regular city surrounded by a town wall along which were hundreds of prayer wheels, leather cylinders three feet high and one or more in diameter, which were nearly constantly kept rotating by the string of pilgrims, which circumambulated the sacred buildings.

Pictures from a 2011 visit of Rocks house, from ASAP in Yuhu.

© text and images courtesy of the Arnold Arboretum Library - Harvard College

Next to the lamasery but separated by a narrow ravine was a cavalry barrack , a large square building occupied by Moslem soldiers who were then commanded by an uncle of General Ma Chi-fu of Hsi-ning who then controlled Ning-hai, that is Ning his and Ch’ing-hai an enormous territory extending to the borders of Tibet in the south, to southwest Mongolia in the north and west to Sinkiang or Chinese Turkestan, and to Kan-su in the East. He was a most powerful ruler and cordially hated as well as feared by the Tibetans of whom the majority under his jurisdiction were nomads. The lamaseries under him were being constantly squeezed including the rich and influential Labrang.

At the time of my visit in 1925, the Moslems had threatened the lamasery and levied enormous fines in rifles and thousands of armes of silver, that it became impossible to longer submit to these exorbitant demands and in protest the great lama, the Laughing Jamb-yang, left Labrang with his father and a retinue of lamas fled into the Cho-ni prince’s territory where he resided in a small lamasery card Pai-shih ngai Ssu or the White rock cliff temple. Labrang without its ruler whose blessing were sought by the thousands of pilgrim nomad Tibetans, because a dead city. The markets practically stopped and the Moslem‘s revenues declined. I had come to Cho-ni and Labrang mainly to obtain letters of introduction from the Buddha to the monastery of Ra-gya on the Yellow River in the west end to the Go-log Chiefs whose encampments were south and east of the great Amnye Ma-chhen Range, west of the Yellow River which I was determined to explore.

© text and images courtesy of the Arnold Arboretum Library - Harvard College

In 1922 I met in T’eng-yüeh (T’eng-eh’ung) Brig. General George Peireira an intreped British explorer who had seen the range a hundred miles to the west of it while on his way from Peking to Lhasa. The General then told me that he thought it was higher than Everest and from these remarks which he must have also made to others, spread the news that there is a mountain in the extreme west of China in Ch’ing-hai Province which surpasses Everest in height. To verify that statement and explore the region botanically was then my determination and the reason which found me then in Labrang.

© text and images courtesy of the Arnold Arboretum Library - Harvard College

The Cho-ni Prince, of whom more anon, gave me a letter of introduction “to the Buddha at the White Cliff monastery and these I presented one spring day in 1925. I was very friendly received by the regent and by the lamas of the small lamasery where I spent two days. After presenting the usual kattag or silk scarf and appropriate gifts to the boy god who rose from his throne at my entrance we discussed the situation then prevailing and the possibility of visiting the Amnye Ma-chhen Range. The regent stated that a tense situation existed between the Tibetans and the Moslems and he suggested I postpone my visit till the following year. However, although he professed to be a refuge himself, he gave me the desired letters of introduction to the great Buddha of Ra-gya Gomba and to the chiefs of the three main Go-log tribes. He further advised me to visit the encampment of all the chiefs of the Tibetan nomad clans from east and west of the Yellow River, who were holding a council of war whether to declare war on the Moslems or not. He thought it a wonderful opportunity to meet these chiefs who were then encamped on the plains of Hei-tso, a lamasery not far from Gho-ni, and for this purpose gave me a letter addressed to all the chiefs who were then under the general authority of Labrang.

I at once acted on the regent’s suggestion and with my entourage and mounted soldier escort furnished me by the Governor of Lanchou I proceeded to Hei-tso where to my great disappointment the camp of the chiefs was being broken up. I did however present the regent’s letter, but the chiefs

informed that they had decided to open hostilities on the Moslems and advised me to postpone my trip to the following year. There were over hundreds tents and hundreds of mounted Tibetan nomads armed to the teeth who had accompanied their chiefs to Hei-tso. There was nothing to do but to return to Cho-ni, await events and make new plans. The Labrang Buddha who had taken up residence in the small lamasery under Cho-ni jurisdiction feIt insecure there for the Moslem general had declared that if he did not return voluntarily to Labrang, he would fetch him by force and bring him back to Labrang. Between Gho-ni and Ti-tao on the T‘ao River there is a high limestone mountain mass, a sacred peak called Lien-hua Shan or Lotus mountain and thither the Buddha fled and there he took his abode on the highest temple on the summit of the peak accessible only by pulling oneself up on iron chains over the vertical cliffs.

His forty cavalry soldier escort provided for his protection by the Lanchou Governor camped at the foot of the densely forested mountain guarding the boy god. It was in Kan-su province proper it was thought that the Moslems would not dare invade the region. As war preparations were then in progress he still felt insecure on Lien-hua Shan, and so finally fled to Ngura, a fierce Tibetan tribe whose encampments were within the knee of the Yellow River. The Tibetan under the jurisdiction of Labrang as well as the Ngura from west of the Yellow River having decided on war opened hostilities and attacked the Moslem barrack at Labrang, the Moslem soldiers at Hei-tso and a general carnage ensued. Every Moslem captured-was hung up by the thumbs, disemboweled alive and the cavities filled with red hot stones.

A big battle ensued on the Ganja plain where the Ngura Tibetans charged a hundred or more abreast, with their thirty foot spears the Moslem infantry; more Moslems were killed with spears than bullets. Unfortunately the Tibetans were not disciplined and their attacks were not coordinated, and furthermore one clan the Amchok tribe, the nearest to Labrang proved treacherous, although they, had agreed to join in the attacks. Yet while all the other Tibetans fought heroically the Amchok Tibetans watched from neightboring hills and then went and robbed the encampments of their brothers in arms. The Moslems, being well trained and disciplined and furthermore religious fanatics, who were bent on exterminating infidels, won the day.

Reinforcements had come from Hsi-ning and the Tibetans were routed. General Ma of Labrang sealed Labrang Honastery to prevent it being looted, and offered a reward of three dollars silver for every Tibetan head, man, woman or child. They rode out into the grasslands west of Labrang killing where ever they went; they came galloping back each one with fifteen heads tied to their saddles which later graced the hitching posts around the Ying-pan. Each Tibetan wears a little queue and by no means of these they braided wreaths of heads which decorated the walls of the large barracks like floral wreaths. There was also some treachery on the part of Lauehou, for the Kan-su provincial government let it be known to the Tibetans that they would receive armed support in their attacks on the Moslem troops. It was at the strength of this that the Tibetans decided to attack, but they were left treacherously in the lurch.

At Hei-tso lamasery, lamas friendly to Moslems, and who had rented houses to Moslem families were strung up, beaten and killed by their own brother monks and their houses burned to ashes. I had visited Hei-tso, a proud lamasery and decidedly hostile to Chinese and foreigners alike, was beautiful situated in the grasslands. I was the on1y foreigner who had ever spent a night under its roof, their unfriendliness was proverbial and haughty and I received a cold reception, but we did not let ourselves be influenced and remained two days. They feared perhaps that should they forcibly eject me they might encounter my armed cavalry escort and the annuity of the Chinese Government. When I returned to Hei-tso the year following, it was in a terribly state, all the temples had been looted, the lamas had f1ed, over eighty had been put to the sword, and its Buddha who turned out to be a renegade was killed by his own people. Everything of brass as doorknobs, chains, the gilded stupa-like adornments of the roofs all was carried off, the idols smashed if made of mortar and melted in if made of metal. In one word Hei-tso was a forsaken ruin. We stayed in the same room we had occupied before, the brass tea pots, water kettles even bowls had gone and the lone lama who had returned related to us a tale of woe.

© text and images courtesy of the Arnold Arboretum Library - Harvard College