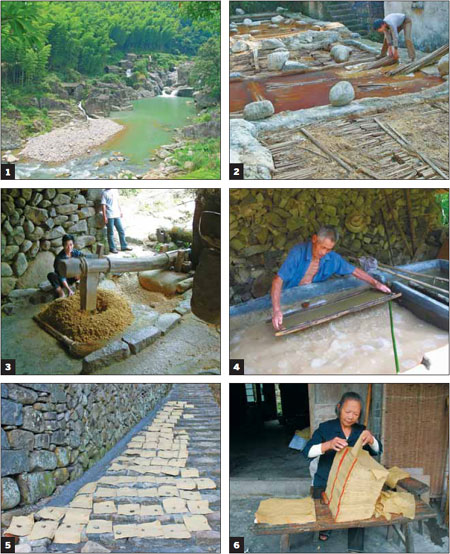

1. An enclave covered with bamboo forest in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province, Zeya is known for its traditional papermaking, which involves more than 100 steps. 2. Fresh bamboo is first soaked in lime water. 3. Soaked bamboo is mashed by trip hammers. 4. A villager dips a bamboo curtain model in and out of a sink filled with bamboo pulp. Then pulp forms sheets of paper on the model. 5. Paper is spread on the road and dried in the sun. 6. Paper is cut into various sizes and is ready for sale. Photos by Zhang Zixuan / China Daily

Zeya mountain area has a 1,000-year-old tradition of bamboo paper making. Zhang Zixuan visits 'Paper Mountain' to learn how it is made.

Villager Zhou Lianxiang dips a bamboo curtain model in and out of a sink filled with bamboo pulp. As she is doing that, the pulp spreads evenly onto the model, forming a filmy piece of material. It is a delicate process. Any slight deviation in the angle of the bamboo curtain or the speed in which it is dipped into the sink, will cause pulp cluster. And that means Zhou will have to start all over again. But the 47-year-old papermaker is an old hand and rarely makes mistakes.

Zhou is the sixth or seventh (she has lost count) generation of paper makers in her family. They live in Zeya mountain area - an enclave covered with bamboo forest - in Wenzhou's Ouhai district, Zhejiang province.

The area, with an approximately 1,000-year-old tradition of bamboo papermaking, is dubbed "Paper Mountain". Compared with other paper making families in Zeya, the Zhou family has a short history of papermaking.

Throughout the generations, they have religiously followed the 109 steps of producing paper manually.

In short, fresh bamboo is first soaked in lime water to destroy the fiber, and then mashed by water-powered trip hammers. This is followed by dipping a bamboo curtain model into the bamboo mixture and by doing so, pulp forms wet sheets of paper on the model. Finally, the paper goes under steamy iron boards to be flattened before they are dried in the sun.

"There used to be 555 water-powered trip hammers and more than 5,000 pulp sinks in Zeya in the olden days," says Shi Chengzhe, director of Ouhai's cultural heritage bureau.

Another villager, Pan Chengshou, is the fourth-generation inheritor of his family's paper making craftsmanship in Shuiduikeng village.

Pan recalls the grand scene when the village's more than 150 households were involved in paper making.

The production sound was music to the ears with paper models making a rhythmic tapping sound against the pulp, joined by the sound of water gushing and trip hammers knocking.

He also remembers vividly the mountain shining in a golden color from afar as millions of pieces of bamboo paper dried gloriously under the sun, which was how the reputation of "Paper Mountain" originated.

"We lived on the craftsmanship during the Mao (Zedong) era," says the 60-year-old.

The faint-yellow bamboo paper, which is rough in quality by today's standard, was considered a luxury item in the 1950s and 1960s, Pan recalls. A local State-owned sundry goods company bought all the paper and supplied it exclusively to big cities, such as Shanghai, as toilet paper.

But over time, machines have taken over the production process. And Zeya paper was only used as paper money to be burned for the deceased.

Pan and his family - like most other villagers - gave up the craft and moved out of the mountainous area during the 1980s, to seek a better life.

In 2005, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage launched the "Compass Project" to preserve ancient China's significant inventions in fields, such as agriculture, water conservation and architecture. Paper making was one of them.

In 2009, Zeya mountain area was chosen as a pilot to demonstrate the tradition of Chinese paper making.

"By preserving the tradition of paper making, future generations will know how their ancestors worked," says Shi, the cultural heritage bureau director.

Besides a paper making-themed museum built in Zeya, the local government invited villagers like Pan to return home to restore their old profession.

Pan's 100-year-old residence, which was abandoned when Pan and his family moved to the cities, was renovated and designated as the demonstration base. All the facilities and tools that stopped working for decades came alive again.

"If not for the restoration, our paper making tradition would have been gone forever," Pan says, adding that he feels great to be making paper again in his hometown.

Pan and his family make about 20,000 yuan ($3,140) every year, which he describes as "not much but enough for a living".

In addition to bamboo paper, the local government hopes to recover other kinds of traditional paper making methods. Four have been successfully retrieved so far.

One of them is bast paper, which is made from the bark of Broussonetia papyrifera trees, which can be easily found all over the Zeya mountain area.

"Bast paper is whiter and tougher than bamboo paper, and is excellent for Chinese ink painting and calligraphy," Shi says.

As more tourists visit the area to find out more about ancient paper making procedures, Shi says, the bureau plans to organize its first Paper Mountain Cultural Festival soon.

Contact the writer at zhangzixuan@chinadaily.com.cn.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| papermakers.jpg | 91.74 KB |